Bird migration along the Strait of Gibraltar: two days, two stories

- Sep 8, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Sep 29, 2025

Every late summer, southern Cadiz becomes the stage for one of the world’s great bird movements. I set out to sample it with a one-day itinerary across several classic watchpoints between Tarifa and Algeciras, spending roughly an hour at each. Four days later, I went back to compare how different weather conditions change what you see.

Where to watch bird migration in the Strait: from Tarifa to Algeciras

The Strait of Gibraltar offers many excellent viewpoints for autumn and spring migration. Among the most popular are Cazalla Observatory, Algarrobo, Punta Camorro, Observatorio Tráfico, Mirador del Estrecho, Punta Carnero, and Playa de los Lances. These sites are spread between Tarifa and Algeciras, each with its own advantages depending on the weather and wind conditions. In this article, I describe my own route across several of them, but all of these watchpoints are well worth a visit during the migration season.

What I witnessed on these two outings was part of the late summer–early autumn migration, when countless birds return to Africa to spend the winter in warmer areas. Migration through the Strait actually happens in two great movements each year. In spring (March to May), birds that have spent the winter in Africa head north to their European breeding grounds. In late summer and autumn (August to October), they make the reverse journey, leaving Europe after the breeding season and crossing back to Africa where food is more abundant and conditions are milder. Some species spend the winter just north of the Sahara — such as White Storks, Black Kites or Short-toed Snake Eagles — while others travel much further to areas south of the Sahara, including Honey Buzzards, Booted Eagles, and Barn Swallows.

The Strait of Gibraltar is one of the most important migration bottlenecks in the world because it offers birds the shortest crossing between Europe and Africa. Many species avoid long stretches of open water, so they funnel through southern Spain where the sea narrows to only 14 kilometres. This natural corridor concentrates vast numbers of raptors, storks and smaller migrants into a relatively small area, making the Strait an exceptional place to witness migration in action.

At first glance, 14 kilometres of open water may not sound like much, especially for large birds with powerful wings. But many migratory species, particularly raptors and storks, rely on thermals — columns of warm rising air — to gain height and travel long distances with minimal effort. Thermals do not form over the sea, so once these birds leave the coast they must cross on flapping flight alone, which consumes far more energy. By funnelling through the Strait, where the distance is shortest, they reduce the time spent flying without thermal support. For soaring birds, this difference is crucial, and it explains why such enormous numbers gather here instead of taking a longer but seemingly possible route.

In hindsight, my timing wasn’t the best for seeing the largest numbers, but it was perfect for illustrating how conditions change the migration. After several days of Levante, birds gather inland and then pour across as soon as the wind eases. That happened at the weekend between my two visits, when thousands of Honey Buzzards and other raptors were seen. My own visits, just before and after, gave me a glimpse of the calmer days on either side of such a spectacle.

The two dominant winds here are known locally as Levante and Poniente. Levante (from the east) blows in from the Mediterranean, while Poniente (from the west) comes from the Atlantic. These names go back centuries and literally mean “east” and “west” in Spanish. Levante is often strong and humid, filling the Strait with haze, while Poniente is usually fresher and drier. Both winds shape the migration: Levante days often concentrate birds inland, while Poniente can bring them low along the coast.

All of the sites I visited are reached along the N-340, the main road between Tarifa and Algeciras. It is a safe but busy road, and it is important to know that there is a continuous white line for long stretches. This means you cannot simply turn around: you often have to continue several kilometres to the next roundabout before coming back. Even if you are a confident driver, it would be dangerous to attempt a U-turn on this road.

The stops on my route were:

Playa de los Lances

Punta Camorro

Observatorio Tráfico

Mirador del Estrecho

Punta Carnero

Punta Secreta

Cazalla Observatory

Playa de los Lances (Thursday)

I arrived a little after eight in the morning at my first stop, with soft light, a pleasant temperature and barely any wind. The boardwalk that leads to the hide is in poor condition, so it is easier to walk alongside it, but access is straightforward and there is plenty of parking space at the entrance. On the beach the bird activity was modest: some Sanderling, Common Ringed Plover and Dunlin. The highlight was a group of eight Greater Flamingos, one adult and seven juveniles, foraging calmly in the shallow water between the hide and the sea. They did not seem bothered by the people passing on the beach. Around the hide, swifts and swallows were active, but raptors had not yet appeared.

Playa de los Lances:

Access: straightforward, though the boardwalk is damaged

Parking: plenty at the entrance

Shade: in the wooden hide

Punta Camorro (Thursday → Monday comparison)

On Thursday the views at Punta Camorro were stunning. The Strait often fills with haze, because warm humid air over the sea mixes with cooler air masses, blurring the horizon. On many days this means that Africa is barely visible, even when the sky above Tarifa looks clear. That morning, however, conditions were exceptional: Tarifa, the Strait itself and the African coast were all in plain sight.

There is a concrete hide here that offers shade and shelter, but the view from underneath it is restricted, and you may miss birds if you stay there. In practice, almost nobody uses it for observations; it is far better to join the other birders who gather in the open at the viewpoint. Parking is simple and close by. The only raptor I saw here that day was a Marsh Harrier.

Four days later the change was immediate. The day was cooler, cloudier and windier, and from the moment I arrived there was a steady flow of birds. Many Booted Eagles passed overhead, joined by Honey Buzzards and Black Kites. Groups of Bee-eaters moved noisily south, and Barn Swallows also continued their journey in smaller numbers. Africa was barely visible through the distant haze, but the air was alive with movement.

Punta Camorro:

Access: easy

Parking: plenty

Shade: under the concrete hide

Observatorio Tráfico (Thursday → Monday comparison)

A few minutes beyond the Sea Rescue Station lies Observatorio Tráfico. The dirt track that leads there is in poor condition, but you can drive all the way to the end and park if there is space, which can be a problem on busy days. The place where birdwatchers gather is just a minute’s walk further, on top of a small hill. If you are worried about your car, you can leave it by the out-of-service cannon and continue on foot.

On Thursday conditions were calm and there was little movement, although I was fortunate to spot a female Goshawk preparing to cross the Strait. On Monday the contrast was dramatic. Raptors streamed past constantly, many flying low through the valley where they could be observed and photographed at relatively close range. Most were Booted Eagles, but there were also Short-toed Snake Eagles, Black Kites, Honey Buzzards and a good number of Egyptian Vultures, including juveniles. A large flock of White Storks appeared, and not long after a smaller group of eleven Black Storks crossed the Strait.

Observatorio Tráfico:

Access: dirt track, driveable but rough; alternative parking by the cannon

Parking: limited at the top on busy days

Shade: none

Mirador del Estrecho (Thursday → Monday comparison)

By midday on Thursday I had reached Mirador del Estrecho. This is a very popular stop, both with birders and with tourists, because it combines excellent panoramas of Africa with easy access and a restaurant terrace that provides shade. The Strait often lies under a veil of haze, caused by the meeting of humid sea air with cooler air masses, and sometimes reinforced by Saharan dust on easterly winds. For that reason, the mountains of Morocco are only occasionally visible in sharp detail. On this Thursday the visibility was unusually good, and the view stretched all the way across.

On Monday the story was completely different. Egyptian Vultures and Booted Eagles were crossing steadily, vanishing into the haze above the Strait, while most of the tourists around me were focused on the views of Africa itself. The bird passage was clear and continuous, in sharp contrast to the empty sky of four days earlier.

Mirador del Estrecho:

Access: very easy

Parking: enough, but crowded at weekends

Shade: on the restaurant terrace

Punta Carnero and Punta Secreta (Thursday)

I continued to Punta Carnero, which lies in Algeciras about twenty minutes’ drive from Mirador del Estrecho. This site can be especially rewarding on Poniente days, but even without much migration it is worth the stop. The lighthouse, the views of Gibraltar and Africa, and the rocky coastline create a dramatic setting. I also drove a little further to Punta Secreta, which offers another striking perspective on the Strait. Birds were few — only a small gull colony, some terns and cormorants — but the landscapes under a deep blue sky made this stop memorable.

Punta Carnero and Punta Secreta:

Access: easy

Parking: very limited at Punta Carnero; a lot of space near Punta Secreta

Shade: none

Cazalla Observatory (Thursday → Monday)

I ended Thursday’s route at Cazalla Observatory. Here, at last, I saw some raptors, though not in great numbers: a few Griffon Vultures, Black Kites, Short-toed Snake Eagles and the occasional Marsh Harrier. Parking is generally easy, although at weekends it can become crowded. A single open shelter with a roof provides some shade, and there is also a visitors' centre with a toilet. Despite the sightings, this Thursday was mostly about the fine weather and beautiful views.

When I returned on Monday afternoon, the activity here had slowed again. Only a few Booted Eagles and Black Kites passed, nothing like the great movements that had taken place over the weekend.

When is the best time to see bird migration in the Strait of Gibraltar?

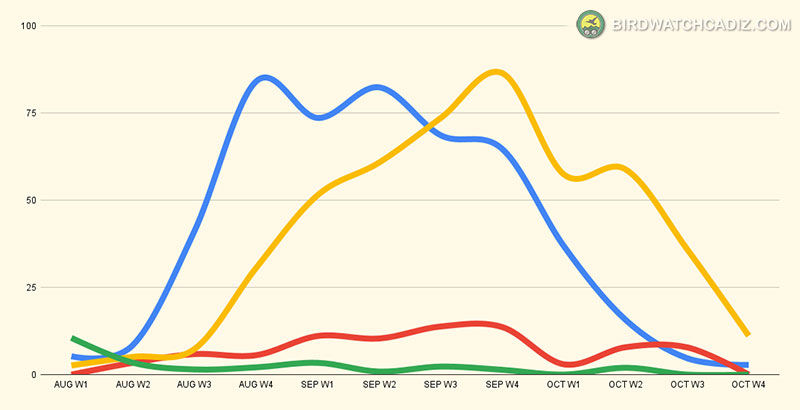

A common question for visitors is when exactly they should come to the Strait to maximise their chances of seeing certain species. The answer depends on the bird. Honey Buzzards peak in September, White Storks usually pass earlier in August, while Booted Eagles and Egyptian Vultures are often still moving well into October. To illustrate these patterns, the following graphs are based on the last ten years of eBird records from Cazalla Observatory, the most intensively monitored migration watchpoint in the area. They show the percentage of checklists in which each species was recorded, week by week from early August to late October, giving a clear picture of when each species is most likely to be seen.

Cazalla Observatory:

Access: easy

Parking: enough, but crowded on weekends

Shade: under the open shelter and inside the visitors' centre

Reflections

These two outings, so close together in time and space, showed me the true character of migration at the Strait of Gibraltar. On one day, the conditions produced wonderful visibility and landscapes but very little passage. Only a few days later, with Levante winds shifting, the birds were suddenly everywhere. The lesson is simple: do not be discouraged by a quiet day, because the very next visit can be completely different. That unpredictability is part of the Strait’s magic, and one of the reasons birders keep coming back.

Comments